Getting Upstream States to Help Fix Downstream Problems

By: Amos S. Eno

Posted on:05/10/2013A condensed version of my speech at the America’s Energy Coast Leadership Forum on May 2nd in Baton Rouge, LA.

For the past 50 years the focus of land and water conservation has been on acquiring public lands-hence the eponymous federal funding mechanism, the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF). What has it gotten us? The four principal federal conservation agencies (NPS, FWS, USFS, and BLM) sport a $35 billion Operations and Maintenance budget backlog and the most of the facilities are generally in a state of gross disrepair. The program focus has been scenic set-asides, not solving the complex ecological problems of a working landscape such as the Mississippi delta. I also think it is high time to put water investments into the LWCF portfolio in this era of repetitive droughts.

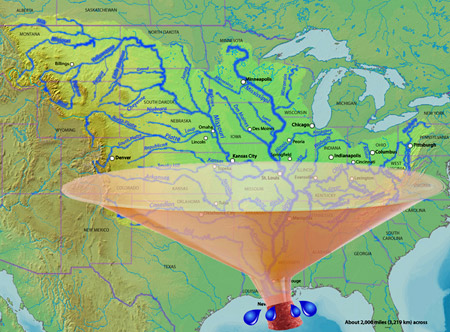

Louisiana’s wetlands are the delta of the vast Mississippi drainage, the fourth largest drainage system in the world encompassing 1,245,000 square miles (nearly 40% of the landmass of the continental United States). Traveling roughly 2,340 miles from its headwaters to the Louisiana delta, the Mississippi delivers an average of 600,000 cubic feet of water every second transporting about 145 million metric tons of sediment per year. Prior to the installation of the many upstream engineering modifications to the Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio rivers and their tributaries the river was transporting over 400 million metric tons of sediment per year before 1900.

When you consider the problems confronting Louisiana’s Energy Coast, you have two closely integrated and related problems of extraordinary complexity. The first problem is the gradual destruction of the Louisiana delta. At the bottom of a very long and wide funnel draining the myriad watersheds of 33 upstream states and two Canadian provinces this 64% reduction in transport load is causing the Louisiana delta many problems that are largely structural:

- loss of barrier islands and chenieres,

- lack of silt accretion,

- salt water intrusion exacerbated by

- canals,

- shipping channels,

- the funnel effect of riverine levees,

- the expanding gulf dead zone.

The Louisiana Coastal Restoration and Protection Authority, supplemented by NFWF’s BP NRDA funding, and the machinations of the Army Corps of Engineers will lead restoration efforts in the delta.

That leaves its close cousin, the upstream problem. The Mississippi runs through the great American Midwest, from Montana to Pennsylvania, encompassing the wheat, soy and corn belts. This vast area of working lands is overwhelmingly privately owned. It is farmed and forested and ranched. How are you going to get this dispersed, idiosyncratic, and highly individualistic constituency of working landscape owners across 33 states to participate and contribute to solving the Mississippi delta’s ecological collapse at scale?

You can’t buy these lands!

Don’t forget … currently the federal government (over 16 trillion in debt) and 48 of 50 states are operating in the red.

You can’t regulate ‘em!

What is in the traditional conservation tool box? Nada!

How do you even communicate across this vast, disparate landscape of private land owners? Easy!

Our solution is to leverage the power of the internet.

That is why we created the Private Landowner Network, a growing portfolio of state conservation centers, and the Conservation Tax Center, designed to assist private landowners with intergenerational land transfer. Resources First Foundation’s (RFF) Private Landowner Network (PLN) is the largest supplier of conservation information, tools, and services on the internet nationwide. Currently, RFF is in the midst of building a state-wide, web-based conservation center for Louisiana, to be called the Louisiana Conservation Connection. We have already built comparable conservation centers for Arkansas and Mississippi. These information centers are designed primarily to enhance and catalyze the stewardship capabilities of private land owners. They provide access to pertinent federal programs (USDA, Interior), comparable state programs, nonprofits (Land trusts, Conservation Districts, Ag extension offices), and for profit service providers (estate and tax attorneys, consulting foresters, mitigation banks, clean energy providers, Community Supported Agriculture, wildlife management consultants, hunting/fishing guides etc.). In addition, we feature the American Carbon Registry, and Earth Partners and Tierra Resources.

That is why we created the Private Landowner Network, a growing portfolio of state conservation centers, and the Conservation Tax Center, designed to assist private landowners with intergenerational land transfer. Resources First Foundation’s (RFF) Private Landowner Network (PLN) is the largest supplier of conservation information, tools, and services on the internet nationwide. Currently, RFF is in the midst of building a state-wide, web-based conservation center for Louisiana, to be called the Louisiana Conservation Connection. We have already built comparable conservation centers for Arkansas and Mississippi. These information centers are designed primarily to enhance and catalyze the stewardship capabilities of private land owners. They provide access to pertinent federal programs (USDA, Interior), comparable state programs, nonprofits (Land trusts, Conservation Districts, Ag extension offices), and for profit service providers (estate and tax attorneys, consulting foresters, mitigation banks, clean energy providers, Community Supported Agriculture, wildlife management consultants, hunting/fishing guides etc.). In addition, we feature the American Carbon Registry, and Earth Partners and Tierra Resources.

Why? Because nationwide 71% of the lower 48 states is in private ownership. In Louisiana 90 % is privately owned. This is a woefully underserved conservation marketplace. Few organizations are effectively bringing conservation goods and services to this critical constituency in a comprehensive and coherent fashion as it relates to what comes down the river through the state and into the Louisiana delta.

Since this is the Energy Coast Leadership forum, it is perhaps appropriate to look at the congruence between all the private farm, ranch and forest land in the Mississippi drainage and the major shale gas formations. They correlate very closely. If you leave out the California Monterey Basins and the Texas Permian, Barnett and Eagle Ford, almost every other shale formation lies within the Mississippi drainage basin, and all these areas, which are driving U.S. energy independence and resurgence, are on private lands.

In March I gave a speech to the Louisiana Landowners Association where I suggested that the oil and gas industry should partner with the farm, ranch and forest industries to cooperate on a shared agenda for keeping working landscapes productive and restorative. I think this mindset needs to be considered by these heretofore very separate and distinct constituencies.

For the past 20 years we have witnessed a degeneration in the ability of rural America to maintain jobs and working landscapes. This has come at the expense of Metropolitan American constituencies who have unrealistic expectations on how to grow food, to harvest timber and to produce the oil and gas resources that power Americas’ economy.

Margaret Mead famously said: “never underestimate the ability of a small group of individuals to change the world…” We need a small group to coalesce and bring about a renewal of working rural landscapes imbued with a commitment to long term natural resource stewardship and restoration.

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In