Malpai Brings Voluntary Conservation to the Borderlands

By: Amos P. Eno

Posted on:12/15/2014 Updated:02/25/2016The Malpai Borderlands Group is celebrating its twentieth year of fostering voluntary conservation programs in the southwest.

Looking at the borderlands of southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, even from the wide perspective of Google Earth, the most remarkable feature of the region is what it lacks. And that’s a good thing. There are no sprawling subdivisions, nor is there a checkerboard of oil well pads. Rather, the only human presence in this one million acre region between the Chiricahua Mountains and Playas Valley is that of twenty-five ranches.

The Malpai Borderlands Group wants to keep it that way. Celebrating its twentieth anniversary this year, Malpai works to sustain the livelihood of these ranchers and the ecosystems of this unfragmented landscape on which they depend. Working with landowners, Malpai has created conservation easements on fifteen ranches in the borderlands covering almost eighty thousand acres. Additionally, they just applied for a grant through the NRCS’ Regional Conservation Partnership Program to create four new conservation easements.

Comprised of, and led by ranchers, Malpai has established itself as one of the leaders in voluntary, landowner-led conservation. Since its founding, Malpai has been guided by the motto: “We will never do something to someone – it will be done with them or not at all.” According to Bill McDonald, Executive Director of Malpai, this approach has led to greater landowner participation in programs to sustainably manage the land, and a greater enthusiasm for the work.

As evidence, McDonald offered the example of their work with prescribed burns. Malpai has been conducting prescribed burns in an effort to reintroduce fire to the landscape, but they have to be careful not to burn on the land of those who don’t want it. The hope, McDonald says, is that after seeing the voluntary work on their neighbors land, landowners who at first were resistant will think: “Hey, that turned out better than I thought; maybe I’ll get involved next time.”

People can be required to implement conservation practices through regulation, but when landowners “are not really comfortable with what they’re doing, chances are the results will be disappointing to say the least,” says McDonald. “But that’s often the ways things are done out here, especially when it involves federal and state agencies.”

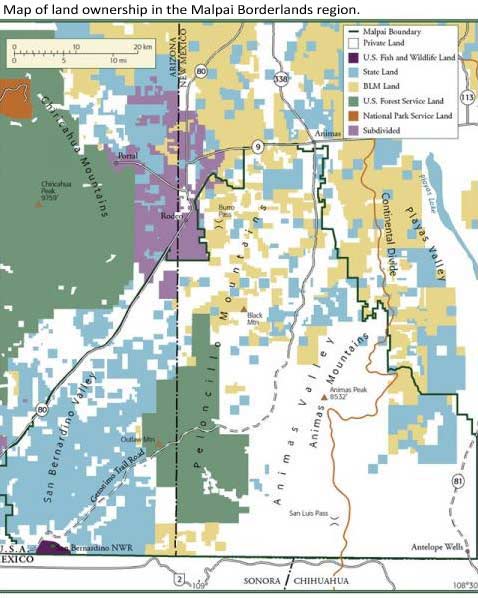

It’s a story that has played out throughout the West; landowners resist implementing conservation practices they perceive as being forced on them by government agencies. And government agencies have a large presence in the borderlands. The States, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management all own land in the region, and ranchers often lease land from at least two of these agencies.

It’s a story that has played out throughout the West; landowners resist implementing conservation practices they perceive as being forced on them by government agencies. And government agencies have a large presence in the borderlands. The States, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management all own land in the region, and ranchers often lease land from at least two of these agencies.

With so many different land management agencies, ranchers in the borderlands would often get conflicting direction from different agencies. For twenty years, Malpai has worked to foster communication and collaboration between landowners and government agencies, and among the agencies themselves.

This collaboration between all parties has been particularly important for endangered species conservation. Malpai set the tone for how they would address endangered species when, in 1996, Malpai board member Warner Glenn went public with his photographs of a jaguar in the borderlands, the first photos ever taken of a wild jaguar in the United States. Further investigation revealed that, although there is a population of jaguars near the Rio Yaqui one hundred and thirty miles south of the border in Mexico, there is not enough suitable habitat in the Malpai borderlands to sustain a population of the big cat. Nevertheless, Malpai works to keep the landscape open, and created a fund to reimburse ranchers for any loss of livestock due to jaguar depredation. Only one claim has been made since the fund was established a decade ago.

With nearly thirty state or federally listed species living in, or migrating through the borderlands, Malpai has also created a multi-species Habitat Conservation Plan and Safe Harbor Agreement for the threatened Chiricahua leopard frog.

While endangered species work on private lands sometimes is perceived as a burden for landowners, that’s not always the case with Malpai. In the southwest, everyone needs water, and collaborative work with state and federal conservation agencies has created water projects that help both the Chiricahua leopard frog and ranchers.

Water scarcity is always a top concern in the borderlands, and much of Malpai’s work goes to mitigating drought and improving the region’s watershed. This effort is epitomized by the building along arroyos of miles of rock structures, which reduce erosion, capture sediment and establish vegetation.

Another vital part of maintaining a viable watershed is healthy grasslands. Working with ranchers, Malpai Borderlands Group has mechanically treated two thousand acres of brush to remove invasive, and thirsty woody vegetation, and used prescribed burns to rejuvenate the region’s grasslands.

Exchanging pleasantries during our conversation, I mentioned that it was thirty seven degrees and raining here in Maine.

McDonald responded: “Well, then I won’t tell you what our weather’s like. But here, we root for rain.”

Postscript:

I attended a Malpai Borderlands Group board meeting in the spring of 1996 as part of my due diligence in providing them a grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. I stayed at the ranch house of Wendy and Warner Glenn. Wendy was the heart and soul of the Malpai for twenty years; part den mother, part administrator, part inspirator. Sadly, she passed away this spring. I tip my hat to Wendy, a true conservation pioneer and I hope her spirit and strength will be carried forward by her Malpai companions.

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In