Restoring Idaho's Lemhi River

By: Amos S. Eno

Posted on:07/21/2015 Updated:07/22/2015Last week, I spoke with Jeff DiLuccia, a fisheries biologist for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game in the Salmon region, of which the Lemhi Valley is a part, to learn more about a project to restore a two mile segment of the Lower Lemhi River for the benefit of Chinook salmon and steelhead.

A few weeks ago, I spoke with Kristin Troy, Executive Director of the Lemhi Regional Land Trust, for our blog Community Conservation at its Best. We spoke mostly about the work Lemhi Regional was doing to help landowners in the Lemhi Valley to conserve their land, but she also mentioned that several landowners were engaged in restoring the Lemhi River and its tributaries where the waters flowed through their land.

Last week, I spoke with Jeff DiLuccia, a fisheries biologist for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) in the Salmon region, of which the Lemhi Valley is a part, to learn more about a project to restore a two mile segment of the Lower Lemhi River for the benefit of Chinook salmon and steelhead, “the two species that we’re really focusing on now in terms of restoring inland fresh water habitat, because they’re listed under the Endangered Species Act and they go all the way to the ocean and back – up to 850 miles in parts of the upper Salmon River,” said Diluccia.

Records show that there were large numbers of salmon spawning throughout the Lemhi River drainage, but starting in the mid-1800s stress on water flow gradually increased as settlers diverted water for agricultural irrigation.

However, it was in the 1950s that mechanical developments really damaged the basin’s salmon habitat. In 1952, a decommissioned railroad bed was transferred to the State of Idaho, which decided to turn it into a highway. Rather than constructing the highway along and over the river, the State decided to reroute the river parallel to the road.

Five years later, the Lemhi River basin experienced one of the highest floods in its recorded history, and local farmers and ranchers decided to constrain the river to prevent future flooding on their pastures. In just one year, they drastically altered one third of the Lower Lemhi River.

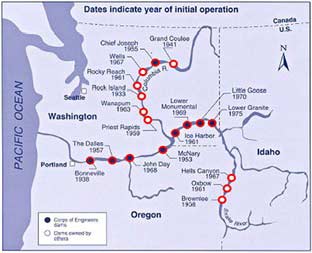

It was in the same year, 1957, that the construction of the first of seven new dams between the Lemhi Basin and the Pacific Ocean was completed. The final dam, Lower Granite, was completed in 1975, and “from that point on, the salmon runs in Idaho really took a nosedive,” said DiLuccia. (The older Bonneville Dam was constructed in 1908, for a total of eight dams in the Federal Columbia River Power System between the Lemhi and Pacific.)

It was in the same year, 1957, that the construction of the first of seven new dams between the Lemhi Basin and the Pacific Ocean was completed. The final dam, Lower Granite, was completed in 1975, and “from that point on, the salmon runs in Idaho really took a nosedive,” said DiLuccia. (The older Bonneville Dam was constructed in 1908, for a total of eight dams in the Federal Columbia River Power System between the Lemhi and Pacific.)

Because the dams are not going away any time soon, work to recover Chinook and steelhead populations is happening away from the dams in what is called off-site mitigation, which brings us to the restoration project in Lemhi.

Interestingly, landowners in the Lemhi valley were proactive in trying to restore salmon populations. In the late 1980s, prior to the threatened listings of Chinook and steelhead under the ESA in 1992 and 1998 respectively, they noticed the decline in fish runs and approached the State of Idaho and asked what they could do about it.

Those meetings resulted in the IDFG writing what was called an irrigators’ plan. While broad, the plan was the first document planning voluntary cooperation among landowners and IDFG.

While still voluntary, DiLuccia says that restoration efforts are now more targeted. DiLuccia says restoration in the Lemhi is two-pronged: “Let’s reestablish the connection to previously occupied but currently disconnected tributary habitat, and let’s improve the quality of habitat that is currently occupied by Chinook and steelhead.”

DiLuccia is developing a project to do that latter on a two-mile stretch of the Lower Lemhi River that runs through Eagle Valley Ranch, owned by my Princeton classmate and previous subject on the blog, Nikos Monoyios.

DiLuccia said that they know adult Chinook and steelhead are migrating through the region, but they’re focused on improving habitat for the juvenile fish that do not have enough good habitat to grow and survive.

“The whole idea is to try and get as many juvenile fish out to the ocean, and in as good a condition, as we can,” said DiLuccia. “The only way to do that is to create better rearing habitat for juveniles.”

Much of the Lower Lemhi has been straightened or narrowed, with what is called rip-rap rock embankments to keep the river from moving naturally, “and that takes away a lot of the slower water and lateral habitat where it intermixes with the vegetation, where these juvenile fish go to hide, but also near the flow which carries a lot of the food,” explained DiLuccia.

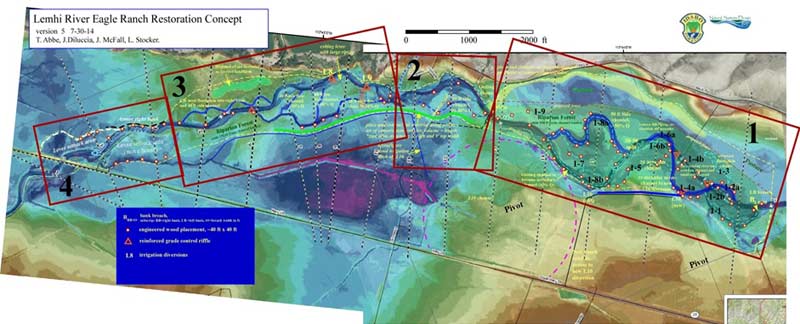

The restoration project on Eagle Valley Ranch will work to recreate the river’s natural processes with main goals: Increase river complexity by developing side channels with lower, slower flow, and creating pools, lateral habitat, and large woody debris behind which the fish can hide; develop a more natural floodplain through rip-rap removal and grading; and restoring the riparian zone with revegetation.

Good rearing habitat for juveniles has become increasingly important because fish that used to simply float to the Pacific with the spring flows now have to swim through the dead water behind each of the eight dams separating the Lemhi from the ocean. If juvenile salmon don’t gain a lot of weight inland, they may not have enough energy once they reach the coastal estuaries, leading to what DiLuccia called latent mortality, or “mortality resulting from passage through the hydropower system that is not expressed until after these fish have passed through the system” (Budy et al. 2002).

Good rearing habitat for juveniles has become increasingly important because fish that used to simply float to the Pacific with the spring flows now have to swim through the dead water behind each of the eight dams separating the Lemhi from the ocean. If juvenile salmon don’t gain a lot of weight inland, they may not have enough energy once they reach the coastal estuaries, leading to what DiLuccia called latent mortality, or “mortality resulting from passage through the hydropower system that is not expressed until after these fish have passed through the system” (Budy et al. 2002).

Bonneville Power Administration, which harnesses the power from these dams, is required by an Act of Congress to mitigate for the ecological losses caused by the dams. As a result, Bonneville has created a number of fish and wildlife programs, and is a source of funding for this project.

Another source of funding is the Pacific Coast Salmon Recovery Fund, which is a congressional appropriation managed by NOAA Fisheries for improving conditions for salmon in the Pacific Northwest. Because Idaho is not actually on the coast, DiLuccia said that for his state to get funding it took some “beating on the table and saying, ‘Hey, we have Pacific salmon too. They swim inland, thus Idaho should be a part or this.’”

The final large source of funding is coming from the Habitat Trust Fund, which was established under the Snake River Basin Adjudication to work with landowners in restoring fish habitat.

The Lower Lemhi River rehabilitation project is broken up into four reaches, the first three of which are on Eagle Valley Ranch. Funding is secured from the SRBA board and Benneville for reaches one through three, and DiLuccia plans to start implementation on reach two this fall, when they will construct a 1700 foot side channel, add large woody debris, transplant vegetation, and plant grasses and trees to restore the riparian area.

To evaluate their progress on this and other restoration projects, IDFG is collaborating with Quantitative Consultants Incorporated on a rigorous monitoring program. Through the monitoring program, IDFG “is addressing limiting factors that are preventing these fish from growing and surviving, and then we can go in and study it and see how we’ve done. That’s a pretty good position to be in,” said DiLuccia.

Additionally, DiLuccia was quick to emphasize that “up here, the salmon swim almost entirely through private lands, so without the participation of the landowners we couldn’t do what we’re doing, and that is improving the conditions for fish to support their recovery.”

Feedback

re: Restoring Idaho's Lemhi RiverBy: Nikos Monoyios on: 07/22/2015My wife Valerie and I are excited to be working with IDFG on this important fish restoration program on the Lemhi River. Jeff DiLuccia has already completed several other projects on Bohannon Creek, a tributary of the Lemhi that runs through Eagle Valley Ranch. We have also recently donated a conservation easement to the Lemhi Regional Land Trust that will protect these important riparian areas from future development and preserve their agricultural and scenic values. We are gratified to see that many of our neighbors in the Lemhi Valley are engaging in private efforts with assistance from IDFG to assist in the recovery of endangered species.

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In