A farm manager in Michigan and an avid duck hunter in Ohio have never met. They have different land, different backgrounds and different objectives for their properties. Still, they are connected by their shared desire to establish productive wildlife habitat while making a living off their land.

That’s a bond that links them, even at different altitudes — from an airplane taking photos at 15,000 feet to heavy equipment toiling at ground-level. With the help of Ducks Unlimited (DU), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) and other partners, Kim Bayer and Mike Bohling have made their properties more welcoming for ducks, deer and countless other animals. In return, those tracts are supporting their way of life.

Bayer is the farmer; Bohling, a waterfowl hunt manager. Each has worked with DU and the Service to learn how to better use the wetlands on their property to promote wildlife and business. A key tool: the Service’s National Wetlands Inventory, which provides detailed information on the abundance, characteristics and distribution of U.S. wetlands.

What Bayer and Bohling have accomplished is a lesson in how conservation and commerce not only coexist but benefit each other.

Bayer’s Ann Arbor property, Slow Farm, promotes healthy wildlife habitat and healthy eating. It’s an organic farm, producing asparagus, berries, flowers, tomatoes, pumpkins and squash for customers to pick themselves. Having a thriving landscape, Bayer said, is good business practice.

“It’s getting back to the idea of a more biodiverse landscape and low-input way of growing food over a long-term period,” said Bayer, who has owned the farm for nearly five years.

Consulting with Bayer, DU scientists used the Service’s wetland maps to select a portion of Slow Farm for wetlands restoration. The project is part of DU’s Great Lakes Initiative, which aims to protect the waters of the Great Lakes and conserve critical habitat for many species of waterfowl.

Bayer worked with DU, the Service and the Michigan Department of Natural Resources to restore 96 acres of what was once a drained and heavily farmed section of land. The tract was never very productive, she said. Now, Bayer has a farm rich not just with produce, but with waterfowl as well. The restored wetland is a favored nesting site for mallards. Bayer also plans to add honeybees to the restored site, creating ready-made pollinators for her produce.

“It’s fantastic that there is this kind of support for restoration like this,” Bayer said. “We are extremely grateful to be able to participate and to try to make it something that adds to the biodiversity in Michigan.”

Bohling’s 100-acre little slice of wildlife paradise is in northwest Ohio, on the western shore of Lake Erie. The Bohlings manage their property for fall waterfowl hunting. They open the land to friends, family and fundraising events for conservation, and make great memories every season.

But those memories — and the family business — faced a threat. Levees installed there nearly a century ago to manage wetland water levels had started to fail. That imperiled a healthy habitat. As water levels fell, wetlands dried up and filled with invasive plant species. That choked out any usable habitat for ducks and other wildlife.

About four years ago, DU stepped in. After using the Service’s wetland maps to identify Bohling’s land for conservation help, DU hired heavy-equipment operators to remove some failing levees while shoring up others. That created a wider, more natural wetland basin and allowed water levels to rise.

“It’s like a switch was flipped,” Bohling said. “There used to be 30 acres of nothing, because of the invasive species. Now, we’re holding 2,000 to 3,000 birds at a time on our property.” Bohling said the greatest surprise has been the response of ducks in the spring, as they migrate from their wintering habitat to breeding habitat.

The resting ducks are such a pleasure to watch that they have prompted Bohling to appreciate his property even more. If the habitat is good for the ducks, it’s good for him, too.

“The spring fly-back is more valuable to us as a property,” he said.

“Looking after wetlands just makes good sense,” said Megan Lang, chief scientist for the Service’s National Wetlands Inventory.

“The projects in Michigan and Ohio underscore the importance of using landscape scale conservation to support high-quality habitat on private land,” she said. “Wetland mapping,” she added, “is crucial to the long-term health of waterfowl populations.”

“Working at the landscape scale is critical for conservation and management of fish and wildlife, especially long-distance travelers like waterfowl,” she said. “Maps of key habitat, like those produced by NWI, are the foundation of landscape scale conservation.”

Technology has helped. As recently as the 1990s, DU and the Service drew pen and ink lines on hard-copy aerial photos to distinguish wetlands. It was a laborious task — a painstaking visual review of hard-copy aerial photographs.

That changed as digital imagery, and computer-based image analysis and cartography became available.

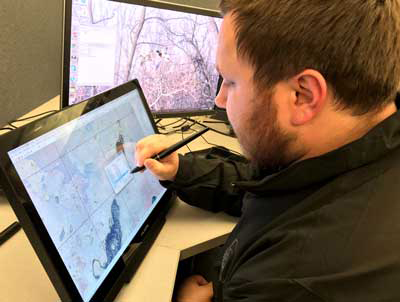

Now, DU’s geographic information system (GIS) experts are testing new approaches to automatically identify groups of wetland pixels, saving valuable time.

“We want to get the biggest bang for our conservation dollars,” said Robb Macleod, DU’s national GIS manager. “If we don’t know where potential restoration efforts are, we can’t target them.”

“The Service and DU have enjoyed a great working relationship over the last 35 years, and we look forward to working together for many years to come,” said Lang.

“The benefits of partnering with DU have been tremendous, not only to our organizations but to environmental conservation,” she said. “The rewards of this conservation are felt by all citizens, in the form of clean and abundant water, reduction of natural hazards, and greater recreational opportunities.”

At least two citizens — one, a farmer in Michigan, the other a duck-hunting enthusiast in Ohio — agree. Bayer and Bohling credit DU and the Service with helping keep their lands working for them and inviting for wildlife. Bohling, for example, looks out on his improved wetlands and sees future generations of ducks landing and taking wing. That’s good for future generations of Bohlings, too.

“I’ve never seen a more successful outcome with my conservation projects,” he said, “and it only gets better every year.”

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In

Sign In